Anwar Ditta: The mother who took on the UK government and won

It is 40 years since Anwar Ditta won her campaign against the UK Home Office and became one of the first to use DNA evidence to win the right to family reunification.

A clipping from the Rochdale Observer newspaper in 1981 about Anwar Ditta’s successful campaign to be reunited with her children who were in Pakistan. Here, she is pictured with her daughter, Samera [Photo courtesy of Anwar Ditta]

A photograph from 1982 shows the legendary late Labour MP, Tony Benn, marching in Trafalgar Square alongside the Namibian revolutionary, Sam Nujoma, the South African freedom fighter Oliver Tambo and a sea of male trade unionists holding banners denouncing apartheid and offering solidarity to the people of Namibia and South Africa. In the middle of this image stands a striking, yet petite lady: Anwar Ditta.

Today, Anwar, 67, is an unassuming housewife of Pakistani heritage who resides in Rochdale, Greater Manchester. But, between 1975 and 1982, she found herself at the centre of an anti-racist movement because of her fearless fight against Britain’s Home Office which had separated her from her three children in Pakistan.

Anwar and Tony Benn (centre) at an anti-apartheid demonstration in Trafalgar Square, 1982 [Photo courtesy of Anwar Ditta]

Anwar’s story came to define an era of Asian anti-racist resistance, due to the explicit institutional racism it exposed within the British government. Her fight against the country’s racist immigration laws was by no means unprecedented. But what separated Anwar’s case from the many others like it was the rainbow coalition of support she managed to garner and her ability to mobilise people both nationally and internationally in her defence.

Her experience exposes Britain’s deeply shameful history of racism and the traumatic consequences many faced as a result of its prejudicial institutions.

Born in Birmingham, the UK’s second-largest city, in 1953, Anwar’s early years were mainly spent in Rochdale, where she lived with her younger sister, Hamida, and her parents.

Anwar’s mother, Bilquis Begum, and her father, Allah Ditta, were from Pakistan, born there while the nation was under British colonial rule. Spurred by curiosity, her father, who was born in 1921, left his teaching job in Pakistan and moved to the UK in the 1950s. When he arrived, he was employed as a bus conductor and foreman in a crystal factory while his wife, who moved to Britain a few years later, stayed at home with their children.

Anwar and Tony Benn (centre) at an anti-apartheid demonstration in Trafalgar Square, 1982 [Photo courtesy of Anwar Ditta]

Then in 1963, Anwar’s parents separated and her father won custody of Anwar and her sister. They were sent to live with their paternal grandparents in Pakistan. Today, Anwar says she has few recollections of this time. She does know that, on arrival, they were enrolled in a local school. But her grandfather, fearing that they would leave the family home and the country if they were educated, objected and they were pulled out of school when Anwar was 9 and Hamida 7.

‘Treated worse than somebody accused of murder’

In 1967, when she was 14 years old, Anwar was married under Islamic law to 22-year-old Shuja Ud Din. His family had been renting a property from Anwar’s grandfather and the two families had become well acquainted by the time Anwar’s grandmother arranged the marriage. The couple had three children – Imran, Kamran and Saima.

Anwar had only very sporadic contact with her mother during her childhood. But, when her mother visited Pakistan in 1975, Anwar expressed her wish to travel back to Britain, her birth country. She also wanted to join Shuja who had been sponsored by a friend to live in Denmark before he moved on to the UK in 1974 where he lived with Anwar’s mother while he waited for her to arrive. Unaware of her legal rights as a British-born citizen to travel back to the UK with her children, Anwar and Shuja agreed to re-marry under British law, find a new home there and settle before applying for their children to join them.

In 1976, by which time they had a fourth child – a British-born daughter called Samera – Anwar and Shuja applied for their three children in Pakistan – now aged 6, 4 and 3 – to come to Britain.

That, she recalls, was when her “nightmare with [the] immigration authorities began”.

The Home Office made them wait two and a half years for the result of their application. In that time, Anwar and Shuja met with countless solicitors, organised pickets and even sought the help of the recently established Commission for Racial Equality (CRE).

Anwar describes how emotionally shattering this time was as “the children [in Pakistan] were very small. My youngest child was breastfeeding when I left.”

Anwar at her Rochdale home in 1980, after the Home Office had refused to allow her three children to come to the UK from Pakistan [Photo courtesy of Anwar Ditta]

In May 1979, the Home Office refused their application because, it said, it doubted the parental relationship the couple had with their children. In its decision, the Home Office stated that the evidence the couple had provided was insubstantial and falsely stated that “no documents or evidence to show positively that she bore three children in Pakistan had been produced.”

The Home Office began to suggest that Anwar’s sister-in-law, Jamila, who lived in Pakistan, was the true birth mother of the three children.

Officials also argued that there was no evidence to prove that Anwar had ever lived outside of the UK and, therefore, no way to prove the couple had married in Pakistan. Instead, the Home Office suggested that documents showing Anwar and Shuja marrying in Pakistan belonged to a different couple entirely who happened to share the same names as them.

One problem was that Anwar’s family had falsified her age on her marriage certificate to enable the marriage to proceed – it stated that she was 20 (the age of consent) at the time rather than 14.

In response to these claims, the couple sent the birth certificates of Jamila’s own six children along with photographs of them and Anwar’s three children standing together. To prove that she had, in fact, lived in Pakistan, Anwar provided officials with further photographic evidence of her, Shuja and their children in the country.

There was also evidence in her British health records which showed no medical files from 1962, when she left Britain as a 9-year-old, until 1975, when she re-entered aged 22 and re-registered with the National Health Service.

Anwar even underwent invasive internal examinations to provide evidence that she had given birth to her children. This “virginity testing” practice was used by the Home Office on many Asian women in the 1970s to allegedly assess their “true” marital status and decide the outcome of their immigration applications. Anwar compares the trauma of this practice to being “abused by consent”.

None of the evidence could sway the Home Office, however.

Anwar with her youngest daughter, Samera, leading a demonstration in Rochdale, November 15, 1980 [Photo courtesy of Anwar Ditta]

The former Labour government Home Office Minister, Alex Lyons, would later explain on the World in Action TV programme in 1981 that Home Office officials often made up their mind on a case before an appeal had even been heard and were inflexible even when new evidence was provided. He stated: “They are seeking to justify the decision of the Entry Certificate Officer. There are many cases where people have produced new evidence and the Home Office have resisted because they are defending an entrenched position.”

Lawyer Ruth Bundey, who would later represent Anwar and Shuja, gave an interview to ITV Granada at the time of the Home Office decision in which she also commented on the unjust way the case had been dealt with. Bundey said: “Anwar is treated worse than somebody accused of murder, in that she is not even given the benefit of any doubt. She is not being asked to prove her case on the balance of probability, which is the normal civil procedure. She is being asked to remove all shadow and vestige of doubt about what has happened.”

In the same ITV interview, Lyons also sympathised with the couple and criticised the immigration system. He claimed that decisions were made “partly by hunch [and] partly by a series of questions which have been manufactured over the years and in the end, although [they] would deny it, [they are] applying a very strict sense of the balance of proof”.

Anwar speaking at a picket in Blackpool in 1980, where the Labour Party’s annual conference was being held that year [Photo courtesy of Anwar Ditta]

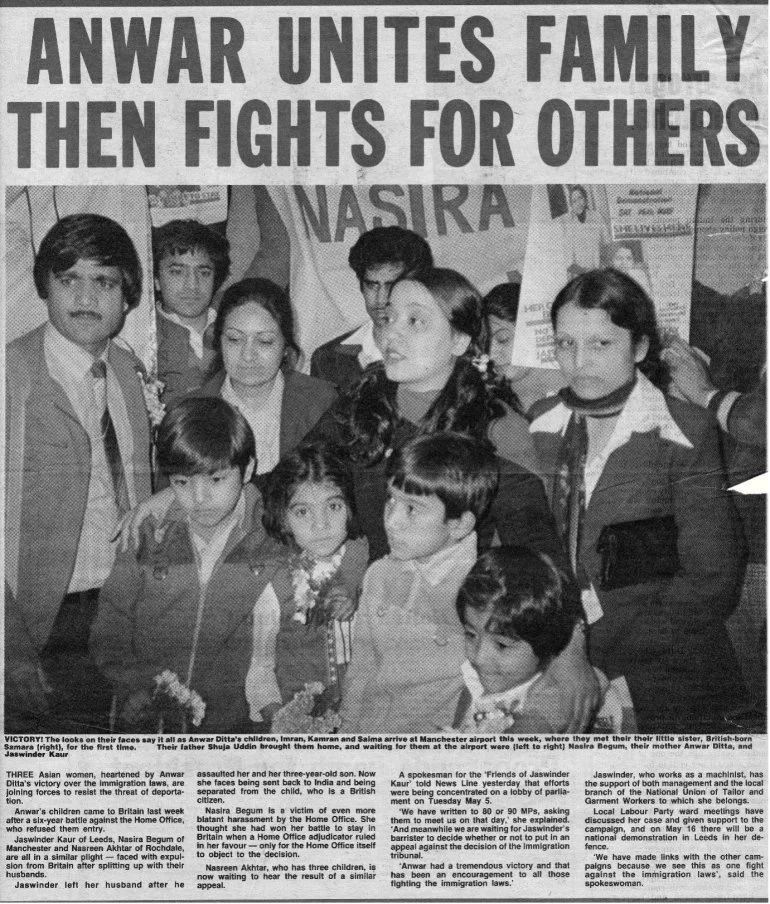

Anwar’s case was first brought to public attention in November 1979 at a meeting in Manchester’s Longsight Library, which was being held to discuss the deportation cases of two women – Nasira Begum and Nasreen Akhtar, both from Pakistan – who were fighting to remain in Britain. Begum was facing deportation after escaping from domestic abuse, while immigration officials had decreed Akhtar’s marriage to her British husband invalid. Before concluding the meeting, the organisers asked the audience if anybody else needed help regarding immigration issues. In floods of tears, Anwar spoke about her predicament and, without hesitation, the audience agreed to support her. It was at that moment that her campaign began.

Non-stop campaigning

The meeting effectively launched the Anwar Ditta Defence Campaign and brought together a rainbow coalition of support that included trade unionists, revolutionary communists, legal organisations, political parties from across the spectrum, the Indian Workers’ Association, and even famous radicals such as actress Vanessa Redgrave.

Within the coalition, the Asian Youth Movements (AYMs) made one of the most significant contributions, dedicating a vast amount of time to implementing a political campaign strategy for Anwar’s case. The AYMs were allied, anti-racist Asian groups which emerged in the mid-1970s in response to interpersonal and institutional racism in Britain. While each AYM group operated independently in various cities across the county, they all represented the broader movement of Asian anti-racism.

Through Anwar’s case, the AYMs saw an opportunity to not only help a distressed mother reunite with her children, but also to expose the brutal racism within Britain’s governing institutions. It was thought that approaching British racism through the lens of a mother would be more effective than simply discussing the issue in broad terms.

Anwar, Shuja and family members with campaign supporter Vanessa Redgrave at a celebration party organised by the Anwar Ditta Defence Committee, 1980 [Photo courtesy of Anwar Ditta]

Another strategy of the campaign was to travel the country publicising Anwar’s case. In less than 18 months in 1979 and 1980, Anwar spoke at over 400 meetings and demonstrations. Despite not having had any prior involvement in political campaigning, Anwar was driven by her deep desire to be with her children. Even for a seasoned activist, this would have certainly been an enormous challenge.

“[The Campaign] used to go to public meetings, conferences, student unions [at] universities. There’s no place that I haven’t been,” Anwar recalls. “I spoke at a lot of meetings [and on] the street. You name it. Every weekend, I used to go down into Rochdale town centre with a [donation] bucket and petitioning, going door to door, begging people [to] please sign my petition.”

Significantly, the campaign made sure to demonstrate the complicity of both the Labour and Conservative Party in creating the hostile and prejudicial immigration system. Anwar’s ordeal with the Home Office had begun under a Labour government, led by James Callaghan, and had continued under Margaret Thatcher’s Conservative government.

Anwar says she even wrote a letter to Thatcher, explaining the pain of being separated from her three children. Anwar urged her, as a mother of two herself, to reflect on the case and show empathy. Despite Thatcher’s assistant confirming receipt of the letter, Anwar never received a response.

Allied groups marching in Manchester in support of Nasira Begum, who was fighting deportation [Photo courtesy of Anwar Ditta]

During the years of their campaign, Anwar and Shuja continued sending approximately £70 ($100 – worth a little over $500 in today’s money) per month to Shuja’s mother who, along with other relatives, was looking after their children. This money was used to ensure they received an education and were well cared for.

As well as bearing the emotional pain of being separated from her children, Anwar speaks about the physical toll it took on her and Shuja. “You know, when we were campaigning, I was working day and night. My husband was working. He was coming back from work [as a welder]. I was taking my little one, who was born here, with me or dropping her off to the next-door neighbour.”

A ‘political numbers game’

In April 1980, a year after Anwar’s campaign began, the Home Office granted her an appeal following legal pressure, as well as the campaign’s demonstrations and petitioning. However, in July, the appeal was refused, largely due to errors made by an inexperienced lawyer who was put forward by South Manchester Law Centre to represent Anwar. The Home Office continued to insist that there were irregularities in Anwar’s case – in particular that her age did not match that cited on her marriage certificate and that she only had photographic evidence of ever having lived in Pakistan.

One of the problems the couple encountered was that they had declared themselves to be single when they entered the UK, in the belief that their Islamic marriage would be considered null and void under British jurisdiction.

Anwar Ditta speaking at an anti-apartheid rally in London in 1982, the year after she had won her case to bring her children to the UK from Pakistan. Tony Benn can be seen beside her [Photo courtesy of Anwar Ditta]

Instead of acknowledging Anwar’s young age (she was 22 when she returned to the UK) and vulnerability at the time and the explanations given, the Home Office opted to denounce her as a liar.

Speaking to the academic Anandi Ramamurthy for her seminal book on the Asian Youth Movement, Black Star, lawyer Steve Cohen describes the Home Office’s decision as being part of a political “numbers game”. Cohen, who was a friend to Anwar and an active supporter of her campaign, explains how the immigration cases of both Anwar and Nasira Begum were assessed by the same adjudicator. While Begum’s deportation was eventually overturned in 1981, Anwar’s plea to be reunited with her children was denied.

‘God knows what hell we are going through’

The appeal verdict came as a crushing blow. Anwar and her husband were denied permission to make any further appeals. Undeterred, Anwar’s defence campaign pressed on by reviewing their strategy and mobilising a new legal team headed by Ruth Bundey, who had recently qualified to practise law and was mentored by the barrister who had represented the Mangrove Nine, a group of Black activists accused of inciting a riot in London’s Notting Hill in 1970, Ian MacDonald QC.

In one of her campaign’s pamphlets in 1980, Anwar wrote: “Why am I going to these meetings? Why am I getting people to help me? Because they are my children. Do you think it is easy to campaign? Do you think that it is easy going out in all weathers to campaign? Do you think it is easy doing all these things? It’s really ridiculous, making black people suffer and destroying their families. What kind of law is this? God knows what hell we are going through.”

Throughout the campaign, Shuja, a quiet man who struggled with his spoken English, took on a supportive but background role to his wife, who was the stronger orator. Aside from her battles with the Home Office, Anwar found herself on the receiving end of racism from members of the public who would verbally attack her on the streets and send her abusive letters through the post. Anwar recounts how she found coping with that [level of abuse] “very hard”.

Anwar Ditta pictured leading a demonstration to highlight her campaign to bring her children from Pakistan to the UK, November 15, 1980 [Photo courtesy of Anwar Ditta]

Anwar Ditta pictured leading a demonstration to highlight her campaign to bring her children from Pakistan to the UK, November 15, 1980 [Photo “I was standing at the bus stop in Rochdale one day, going to a meeting, and I can remember this person recognised me and said ‘why don’t you go back [to] where you’ve come from?’ and I said ‘I come from Birmingham!’. And you know what that person did? That person spat on me… that person spat on me! And the other people that were standing by did not say anything,” she recounts.

Anwar’s heartbreaking recollections of that time expose a very dark moment in British society. The violence she encountered ranged from having strangers pull her hair or swear at her on the streets to having envelopes filled with razorblades posted through her letterbox. These letters, along with other hateful messages sent to her, survive to this day, as Anwar kept a personal archive from the campaign, which she has since donated to the Manchester Central Library.

Despite the mountain of opposition she faced, Anwar continued fighting to be reunited with her children. But this took a toll on her and Shuja’s livelihoods. Anwar recounts working in a Marks and Spencer’s factory at the time and being told to give up her job due to the publicity surrounding her case and her need to take time off to attend meetings for her campaign.

‘They said a woman’s place is in the house’

As well as the physical toll the campaigning took on the couple, Anwar tearfully describes the financial hurdles they faced. “We were supporting [the children] back home, we had a mortgage to pay here, we were phoning [Pakistan]… our phone bill over one three-month period came to over £500 (just over $700 or – in today’s money – around $3,100). Then going to meetings, getting posters made, [attending] demonstrations, leaflet-making, going door-to-door, collecting signatures. It was very hard – very hard.”

She adds: “The more the Home Office were determined to say no, the stronger I [wanted] to fight, because they were our children. It was hard. What the Home Office put me through, I can never forget. They abused me.”

Publicity material to highlight a demonstration in support of Anwar Ditta’s campaign [Photo courtesy of Anwar Ditta]

Anwar describes how looking at her children’s photographs and listening to their tape recordings gave her the strength to keep fighting. She also emphasises the importance of the public support she received. “The public gave me the strength, the mothers out there gave me the strength, the [positive] letters gave me the strength, the students that came on demonstrations… I can never forget the public support every time I went out.”

Before her case, she says she was “just an ordinary housewife. Just cooking and cleaning and working, that’s all I was”. However, as time went on, Anwar became a high-profile figure. That had ramifications in her community, among people who felt she did not meet the cultural expectations of a Pakistani woman at that time.

Anwar explains that many within the Asian community failed to support her and her husband during their campaign. “They said a woman’s place is in the house not campaigning, [but], I said, ‘I don’t give a damn what anybody thinks’.”

‘Children sent us their pocket money’

However, today, Anwar recognises how significant her case was in empowering other Asian women. She says: “I think [the campaign had] a big impact on the community. I just continued to struggle and won the case. That gave a lot of courage to women.”

The extraordinary support garnered for Anwar is evident by the unusual coalition of solidarity that was formed. “People from all backgrounds, from every religion, every political party supported me.” Support not only came from within Britain, but also further afield, as seen through the uplifting poem written for Anwar by Irish Republican prisoner Bobby Sands in August 1980. The poem poignantly began with the sentence: “Unity is stronger than courts.” (Sands died after 66 days on hunger strike on May 5, 1981. He was 27 years old.)

From the outset, Anwar was determined to form a campaign that transcended traditional political divides. “I said, ‘I want everybody’s help’ and they were there for me. I want[ed] people to help me as a mother.” Anwar is tearful as she remembers the help her family received during their legal battle. “People sent me money, children [and] students sent me pocket money… unbelievable.”

She credits the “youngsters out there [who] knew a mother was struggling. [who] believed in me [and who] walked beside me”.

A breakthrough came in the form of Granada Television when its World in Action programme approached Anwar. The producers not only covered the efforts of Anwar’s campaign in Britain, they also flew to Pakistan to film Anwar’s children. While in Pakistan, the documentary filmed Anwar’s lawyer, Ruth Bundey, collecting further evidence in the form of documentation, written testimonies and blood tests from Anwar’s children. This was what would turn the case in the couple’s favour.

Anwar’s was only the second immigration case to make use of blood testing. The first had been that of Abdul Azad, a man the Home Office had accused of being in a marriage “of convenience” and of bearing no relation to his two children. The use of such tests in Anwar’s case – and whether they should be employed in others – was even discussed in parliament.

While blood testing and other DNA evidence is commonly used in immigration cases today, it was Anwar’s case which inspired many other families to push to use similar means of proving their familial relationships.

Ultimately, the injustice perpetrated by the Home Office was on full display in March 1981 when the World In Action programme was aired on ITV Granada.

Publicity material to highlight a demonstration in support of Anwar Ditta’s campaign [Photo courtesy of Anwar Ditta]

The following day, the Home Office overturned its decision as a result of the pressure caused by the documentary. Much of the evidence collected by Bundey and filmed for the programme had previously been offered on countless occasions by Anwar and her husband but the Home Office had dismissed it all.

Reunited at last

In April 1981, Anwar, Shuja and their five-year-old daughter, Samera, were reunited with Kamran (11), Imran (9) and Saima (8), at Manchester airport. A photograph taken on the day shows Anwar holding her four children close as she addresses the media with the familiar, stoic expression she had learned to put on during the traumatic years of the campaign.

While the campaign was a significant event in the history of British anti-racism movements, Anwar remains haunted by the trauma she endured. She describes how those years of separation caused issues in her relationship with her three eldest children as they found it difficult to bond with their mother once reunited. “You can never prove to your children [how much] you love them because there’s that gap,” she says now.

Coverage of the family’s reunion at Manchester Airport in April 1981, Rochdale Observer [Photo courtesy of Anwar Ditta]

In her interview with Al Jazeera, Anwar describes the mental toll those years took on her and how viscerally hurt she feels when reflecting on her experience. She says: “The damage that [the Home Office] caused me is a big one. I will never forget that. It’s been a torture, but the damage that they caused in the relationship between me and my children… that’s a different thing.”

Anwar’s experience has driven her to be an outspoken defender of others victimised by the Home Office. She speaks at length about her dismay at the way migrant communities in Britain continue to be treated by the government despite their contribution to society. “If you look at it, people go to different countries to have a better life. They don’t just go to other countries [to] get freebies. They work hard.”

A mutual struggle

Her painful experience left her questioning what it means to have British nationality. “I came to this country thinking it was my home,” she says. “Well, in the end, it was not my home. They never treated me [like this was] my home. You know, they say your British nationality is worth everything … I think it’s worth nothing really.”

In a plea to British policymakers, Anwar urges them to “think before you make immigration laws, how it’s going to affect families, how it’s going to destroy their lives, how you are going to divide them. It’s been 40 years now [and] my life hasn’t been put together. I’m 67 now and it still affects me”.

Today, Anwar spends her time educating others by sharing her story and by donating campaign material to local archives and museums.

She lives with her youngest daughter, Hamera, who was born after the campaign, her son-in-law, Junaid, and her three grandchildren, Rais, Esah and Aizah. Her other grandchildren, Zeyn, Mohammad, Harris, Ibrahim and Imaan have also shown an interest in her campaign and she enjoys sharing her archive with them. As during the campaign, her husband Shuja, who is currently in Pakistan, remains a quiet and private man but, the couple say, they have a lot of mutual respect for the struggle they endured together.

SOURCE: AL JAZEERA

By Bryan Knight